Happy New Year! As a new year gift, here is one of the stories I wrote when my family lived in India. This one happened in July of 2004, when the coconut cutter came to out house. One caveat to this tale – I now love Coconut Water!

Blessings and Namaste,

Kelley

“Madam, the coconuts, they are ready. It is dangerous. They may fall on children.”

I looked out the kitchen window at the tall, tropical palm tree in my side garden. Mary, my housekeeper, was correct. Coconuts had fallen from the tree at least twice in the last three days. Each fall was preceded by the splintering of wood and followed by a resounding thump, as another coconut or two hit the ground close to one of our terraces. And the height from which the coconuts had to fall would make a direct head hit painful. This was not a safe situation for my three children.

“How do we do to get the coconuts out of the tree, then?” I asked Mary.

“Ask Siva, he will get coconut cutter.”

Aha, a coconut cutter. Of course. Makes perfect sense. But as we did not have those guys in Ohio, I did not know they even existed. Only four weeks earlier, my family had moved to India from Cincinnati, Ohio. My husband’s job had brought us to this foreign land and we were all still adjusting to the myriad changes in our daily existence.

Every morning, my husband, James, set off for work with our driver, Siva Kumar, at the helm of our green Toyota Qualis. James’ work involved the proper establishment of a business presence in India for the large corporation which employed him. As he navigated the business world, the kids and I navigated Bangalore, bouncing about behind Siva in the Qualis as we explored this crowded, noisy metropolis, and figuring out how to complete domestic chores, like getting rid of the ripe coconuts before someone received a nasty bonk on the bean. We still had lots to learn about our new home.

We had come to India in June. It was hot, sunny, and still dry. Soon the monsoon rains would start, cooling the city after the summer heat and washing the red dust away from every uncovered surface. Our villa was made of concrete, covered in stucco, and painted white. With its thick walls and pale exterior, we stayed comfortable inside. Outside we had several terraces in a sizeable garden, which we shared with our ant neighbors. Sitting under shade in the afternoon, our family enjoyed chilled beverages and tropical weather, returning inside at the first sign of dusk and the first whine of a mosquito. We had huge plants around the grounds and the flowers bloomed in profusion. But my favorite plant in the garden was the towering palm tree. It was so different from the trees in Ohio.

I had watched the coconuts on the palm tree turn from a pale green to a gray and then to a black with what looked like coarse hair covering them. When they reached this ugly, black color, they were ripe. And on this bright morning, with a maternal picture of potential disaster in my mind, I went in search of my driver, who had returned to the house after the morning commute to the office. He would know all about the coconut cutter. Fortunately for me, he knew about almost everything in India and this was good because in India, I knew almost nothing.

Siva agreed with Mary. “Yes, madam, the coconuts should be cut. I will contact the guy. He will come to cut them out.”

“How soon can he come?”

“I don’t know, madam. He lives here only. I will check.”

“Yes, Siva, please do.”

Siva nodded his head from side to side. This was the first thing that I noticed about people in India, aside from their beautiful dark eyes, deep brown skin, and big smiles. The Indian people nod from side to side, not up and down for “yes” or back and forth for “no”. The difficult thing about the head bobble, as we called it for lack of a better term, is that it can mean yes, no, maybe, or I know what you are saying but don’t agree. I usually just picked which answer I wanted and decided that was what it meant. In this case, Siva had agreed to get a coconut cutter.

Just a few days later, the coconut cutter and his assistant arrived on a motor scooter. He was a scrawny little man with a narrow face, and stringy looking arms and legs. The biggest thing about this man were his eyes, big, dark brown eyes that crinkled and smiled at the white lady and her pale blond children.

He was dressed in a big white shirt and a piece of blue cloth was tied around his waist and up between his legs, like a cross between a skirt and shorts. Many men wore this cloth, called a lungi. Sometimes I’d noticed that the fabric was simply tied like a skirt. For the sake of modesty and convenience, I was glad to see that our coconut cutter had tied his lungi between his legs, for my children and I discovered that he had to shinny up the coconut tree to get to the ripe coconuts.

The kids and I watched, fascinated, as this small man walked over to our very tall palm tree and looked up. He said something to my driver, Siva, in Kannada, the local language in Karnataka state, where we lived. Siva answered. I asked what they said, but both just ignored me. What could I do anyway, but watch?

One must remember that in India, safety does not mean much. Getting the job done is the important thing. And, in the case of coconut cutting, there are no safety nets to catch someone if he falls. Bearing this in mind, we watched as this tiny man prepared to scale our tree.

His first action was to encircle the circumference of the tree with a long cloth, which resembled a bath towel. His arms embraced the tree, as he kept hold of both ends of the towel and began his climb upwards. What were at first skinny little legs sticking out of a bunched up skirt, were suddenly strong, sinewy limbs that moved gracefully, powerfully, up the trunk of the tree. As he ascended the tree, he tossed the cloth a bit above and used it to pull himself up. Added to his burden was a large, scythe- like instrument which he needed to cut down the coconuts.

Finally, the coconut cutter reached the top of the tree. He smiled down at us from that great height, yelled something down which may have been the Kannada version of “timber” and began to cut the ripe coconuts. As the fruit fell, it thumped loudly on the ground. Time and time again, great bunches of coconuts hit the ground. As one section was completed, the cutter shimmied over to the next part of the tree to be sheared.

At one point in the process, Siva came over and offered a sample of coconut water to my children and me.

“Good for health, Madam,” Siva said. “You should try.”

“What do you think, kids?” I asked.

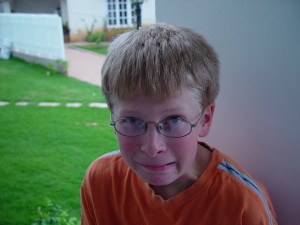

“I don’t know, mom,” answered Andrew, who, at eleven, was uncertain about this adventure his father and I had forced upon him. “It might not be safe to drink.” He tended toward caution in his new Indian environment.

Shannon and Jonathon, his younger siblings, shook their heads a definite ‘no,’ following Andrew’s lead.

“Hey guys, we should try it. Is it good, Siva?” I turned and addressed our driver.

“Very good, Madam. All here drink this. You see stands at side of road to sell. Is very popular.”

“Well kids, everyone in India can’t be wrong. I say let’s give it a try.”

Using a large knife, Siva broke open a coconut. I sent Andrew into the villa fetch some cups, and Siva poured the liquid in.

“Who’s going to try first?”

“Andrew,” volunteered Shannon, then eight. Both she and Jonathon took a step away, grinning and pointing at Andrew.

“Yeah, Andrew,” agreed Jonathon, who, at four, viewed his older brother as a brave, big boy, capable of anything.

Andrew looked at me and I smiled back. “Come on, buddy. It’ll be fine. And then you can tell Dad you tried it first.”

“Fine,” agreed a reluctant Andrew.

Coconut water is not pretty. It looks like water mixed with a bit of milk. Unfortunately, the liquid did not taste much better than it looked, and Andrew’s face relayed to the rest of us his negative opinion in a hurry. He appeared to be in pain, like someone who had just eaten a lemon while hearing fingernails scratch down a blackboard. Based upon Andrew’s response, Shannon and Jonathon declined to try the coconut water. I tried out of politeness and attempted to mediate my facial expressions – but I had to agree with Andrew, it was pretty awful.

Once the coconut cutter was finished with his job, I inquired as to payment. Siva assured me that no payment in rupees was necessary. Instead, it was customary for the cutter to take the coconuts to sell. That worked for me.

I never actually met the diminutive coconut cutter. He smiled and waved as he left, all of the coconuts somehow stacked on the scooter behind him, one man riding at the very back, holding onto the earnings.

Our tree was cleaned of the dangerous coconuts for a time. But, the next time I heard the thump of a coconut in the side garden, I knew that soon, it would be time for a visit from the coconut cutter.